If you’re a systems engineer, you’ve definitely seen the word TIME_WAIT before.

A single ss -tan command will easily show hundreds of them.

At first glance, most people think, “Isn’t this just wasting resources?”

But the truth is, it’s not some meaningless leftover —

it’s a stabilization phase TCP leaves behind to ensure that every last byte of data has been safely exchanged.

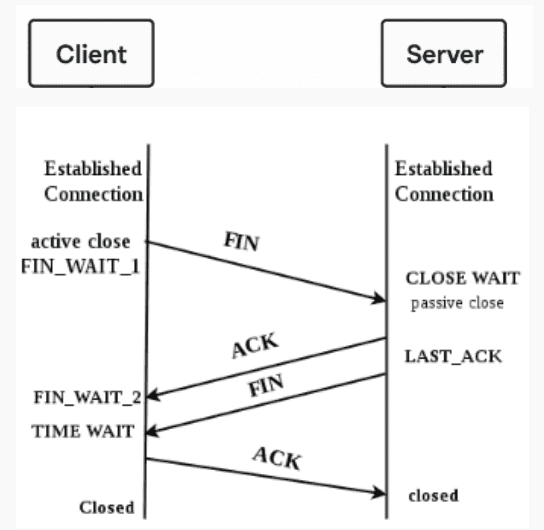

TCP termination is not a shutdown — it’s a cleanup process

A TCP connection doesn’t just end; it’s carefully cleaned up.

When either side wants to close a connection,

the client and server exchange FIN and ACK packets to confirm

that all transmitted data has been received properly.

This is known as the 4-way handshake.

The side that initiates the close — usually the client —

enters a short waiting period afterward.

That waiting period is called TIME_WAIT.

The socket may look closed,

but from the kernel’s perspective, it’s still verifying

whether the final ACK was successfully received.

If the peer retransmits a FIN due to network delay,

the socket can momentarily “resurrect” itself to respond again.

In other words, TIME_WAIT is a short afterlife that ensures a clean goodbye.

How much system resource does TIME_WAIT actually consume?

The biggest misconception about TIME_WAIT is that it wastes system resources.

In reality, the overhead is negligible on modern Linux kernels.

Each TIME_WAIT socket is represented by the tcp_timewait_sock structure,

which contains only minimal data — IP addresses, ports, timestamps, and sequence tracking.

Each entry takes only a few hundred bytes.

Even if tens of thousands of TIME_WAIT sockets exist simultaneously,

the total memory usage amounts to only a few tens of megabytes —

trivial in a server with several gigabytes of RAM.

In other words, TIME_WAIT is a small price for guaranteed reliability.

Forcing the kernel to shorten or reuse these sockets

through options like tcp_tw_reuse can lead to rare but critical issues —

such as invalid session reuse, data corruption, or client port conflicts.

How long does TIME_WAIT last? About 60 seconds — hardcoded in the kernel

The TCP specification defines MSL (Maximum Segment Lifetime),

the maximum time a packet may remain alive in the network.

TIME_WAIT persists for twice that period (2×MSL).

In Linux, this value is hardcoded in the kernel source — roughly 60 seconds.

It cannot be tuned through /proc or sysctl.

This timeout is a system-level safety mechanism,

not a performance parameter you can safely tweak.

“Doesn’t it consume memory?” — Let’s do the math

Each TIME_WAIT entry is lightweight — a tcp_timewait_sock structure

holding just enough state to verify retransmissions.

Depending on kernel configuration, that’s roughly 160–200 bytes per socket.

Even tens of thousands of them together

consume less memory than a single page cache buffer.

In short, TIME_WAIT is protection overhead, not waste.

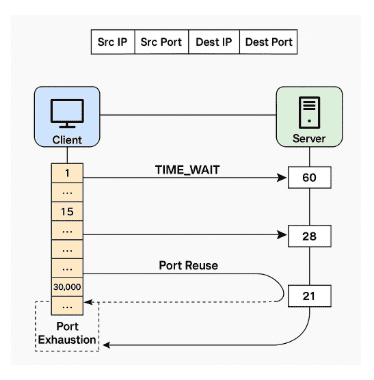

TIME_WAIT doesn’t slow your server — port exhaustion does

A large number of TIME_WAIT sockets does not slow down the server.

The kernel keeps them in a separate space and cleans them up automatically

with almost zero CPU scheduling cost.

The real issue is port exhaustion on the client side.

If a client repeatedly opens thousands of short-lived connections

to the same server in rapid succession,

it can run out of available local ports.

In Linux, the default ephemeral port range

(/proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_local_port_range)

is usually 32768–60999, though it can vary slightly by kernel version or distribution.

Once all ports are occupied — typically by sockets in TIME_WAIT —

new connections may fail or be delayed.

But that’s not because TIME_WAIT is “slow” —

it’s simply a client-side design flaw.

TIME_WAIT and port exhaustion — safe for servers, risky for clients

TIME_WAIT does not cause port depletion on the server.

A server binds to a single port (e.g., 443),

and every incoming connection is handled via a new socket (file descriptor).

In other words, the server keeps one port open but manages thousands of sockets on it.

TIME_WAIT count does not affect the server’s port usage.

The client, however, assigns a new ephemeral port

for every outgoing connection within its local port range.

If it opens connections too quickly,

those ports become temporarily locked in TIME_WAIT

and unavailable for reuse until they expire.

TCP connections are uniquely identified by(src IP, src port, dst IP, dst port, protocol).

This allows port reuse when connecting to different servers or destinations,

and modern Linux kernels also handle safe port recycling internally.

Options like tcp_tw_reuse are mostly obsolete —

today’s kernels manage it automatically and safely.

To summarize:

Port exhaustion is an application design issue,

and it happens only on the client side — never the server.

tcp_tw_reuse? tcp_tw_recycle? — Forget about them

In the past, engineers enabled tcp_tw_reuse or tcp_tw_recycle

to force TIME_WAIT socket reuse.

But those options are no longer needed —

and tcp_tw_recycle was removed in Linux kernel 4.12.

Modern kernels (5.x–6.x) have improved TIME_WAIT management

to safely recycle ports when necessary.

Reducing TIME_WAIT manually is no longer an optimization —

it’s a risk.

The kernel already knows the right balance.

TIME_WAIT — TCP’s last act of integrity

TIME_WAIT is not a problem; it’s a sign of correctness.

It shows that your system is shutting down connections properly

and that the kernel is ensuring no data is lost.

Trying to remove it is like cutting the seatbelt

because you think it slows you down.

Summary

- TIME_WAIT is a normal part of TCP connection termination.

- Its duration is about 60 seconds, hardcoded in the kernel.

- The memory and CPU impact are minimal.

- Port exhaustion is an application design issue,

and it occurs only on the client side. - Forcing socket reuse is unnecessary and risky.

- Having many TIME_WAIT sockets is a sign of a healthy network stack,

not a problem.

TIME_WAIT keeps the door slightly open

until all in-flight packets have disappeared.

Close it too early, and you risk cutting off data still on the wire.

It’s not inefficiency —

it’s TCP’s final act of reliability.

🛠 마지막 수정일: 2025.11.12

ⓒ 2025 엉뚱한 녀석의 블로그 [quirky guy's Blog]. All rights reserved. Unauthorized copying or redistribution of the text and images is prohibited. When sharing, please include the original source link.

💡 도움이 필요하신가요?

Zabbix, Kubernetes, 그리고 다양한 오픈소스 인프라 환경에 대한 구축, 운영, 최적화, 장애 분석이 필요하다면 언제든 편하게 연락 주세요.

📧 Contact: jikimy75@gmail.com

💼 Service: 구축 대행 | 성능 튜닝 | 장애 분석 컨설팅

💡 Need Professional Support?

If you need deployment, optimization, or troubleshooting support for Zabbix, Kubernetes, or any other open-source infrastructure in your production environment, feel free to contact me anytime.

📧 Email: jikimy75@gmail.com

💼 Services: Deployment Support | Performance Tuning | Incident Analysis Consulting

답글 남기기

댓글을 달기 위해서는 로그인해야합니다.